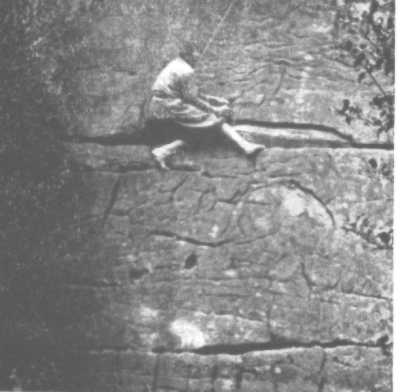

Long Layback

IT is a common complaint among those who live near London that there is no climbing ground within reasonable distance of their homes, for, unlike those who live in the Midlands, they have no gritstone outcrops where they can spend their week- ends. In peacetime, when motor and faster rail transport were available, Wales or even the Lake District was quite feasible on a normal week-end; such visits, providing the regular practice which is so essential in rock-climbing, are now almost impossible, and a satisfactory substitute is hard to find. Thus it appears reasonable to devote space in this Journal to what would in normal times be a rather trivial subject, namely a group of rocks near Tunbridge Wells, which do provide a number of climbs; and although admittedly much of their merit lies in their accessibility, the climbs are of real interest, and certainly deserve attention.

Of late the number of climbing visitors to these rocks has been increasing, and has included a few Cambridge parties. To these and any others who may be intending to spend a day on Harrison Rocks, some brief notes on the type of climbing to bc expected may be of use, though anything in the nature of a complete guide would be giving the rocks a status they do not deserve. Two guidebooks have already been written on them: one by the Mountaineering section of the Camping Club of Great Britain, and the other by Mr. Courtney Bryson. Both are now out of print. In addition to the section on Harrison Rocks, Mr. Bryson’s book also contains information on several other rock outcrops in the district, none of which are really worth a separate visit, unless one happens to live nearby.

The first things the prospective visitor will want to know are the exact whereabouts of the rocks, and the easiest way of reaching them from London. They lie about six miles to the south of Tunbridge Wells, and as they are not marked on the Ordnance Survey map, it is as well to obtain directions locally for the last stage of the journey. They are best approached from Groombridge Station, from which they are perhaps half an hour’s walk. Trains from Victoria to this station and to Tunbridge Wells are frequent, if not fast. The rocks are situated on a hillside, at the edge of a wood, and although they are fairly well known to the local inhabitants, one is not much disturbed by sightseers or picnickers. Most climbing parties spend only one day here, returning home the same evening, but there is a really excellent cave, dry and well provided with firewood. It will hold three people in comfort, and is well known to habitués of the rocks. Apart from this rather primitive shelter, the nearest accommodation is at Tunbridge Wells, the inn at Eridge station being of interest only to the thirsty.

The rocks themselves form a continuous cliff a quarter of a mile or so in length, and averaging thirty feet high. The rock is sandstone, but hard of its kind, and firm. Consequently rubbers are the normal, and in fact the only suitable, footgear, boots being both useless and damaging to the holds. As the cliff is composed of a number of rounded bulges set one on top of .html, there are few incut holds, and overhangs are much in evidence. As a result, the face climbs are as hard as, or harder than, they look, and exposed after a fashion. The general structure of the buttress is seamed with cracks and chimneys, and laybacks are very common. A characteristic feature is the number of narrow passages running back from the cliff frontage, often for a considerable distance. These are narrow, with vertical walls, and while their grassy floors make paths to the top, the passages themselves make excellent chimneys. In one or two cases, two or more converging passages sever a buttress completely from the rest of the cliff, and in one such at least the top is accessible only by climbing, or by jumping across the passage, a somewhat frightening procedure.

There are about thirty climbs known to the present writer, but many of these scarcely deserve a mention, because they are either too short or too uninteresting, occasionally both. Nearly all the better climbs are hard, certainly worthy of a better name than boulder problems, and although it is of course impossible to classify them, it may be said that most would certainly be "severe" or "very severe" by Welsh standards. It is the custom here to climb on a rope held from above, and this is undoubtedly wise in most cases, until one has mastered the many trick moves that abound, Strong fingers are a great asset. Several of the harder climbs have never been led.

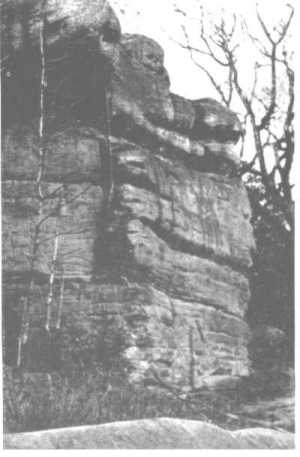

The next

seventy yards of rock are dirty and usually wet, though they probably

have climbs on them. At the far end of this section is a nose of rock,

partly transformed into an island by a deep passage. The corner of this

buttress has a curious shape, and is known as Wellington’s Nose. By chimneying

up the outside of the passage, one can move on to the buttress where it

lies back at a feasible angle; above this is a big overhang, which gives

the climb its name. There are good holds above, and the overhang is short,

so that the move is not as hard as it appears. Further along the passage

the walls are narrow and straight right up to the top, and simple back-and-

knee work will suffice the whole way.

Fifty yards beyond Isolated Buttress is a large cave with a partially deficient roof. This is known as Big Cave, and many excellent scrambles are to be had both inside and outside it. The best is a right-angled crack beyond it, which may be climbed by a layback to the floor of a small cave formed by a fallen block. The difficulty lies in the move out of this, the only available hold being out of sight and at least a foot higher than the average man’s reach.

The rocks

beyond this point become broken and overgrown for perhaps fifty yards,

until Half-Crown Corner is reached. This is a curious horizontal groove

five feet from the ground, and the problem is to cross it from left to

right and then ascend the buttress beyond. The best method to adopt in

the scoop, which is now heavily marked by those who have fallen out, is

to press with one’s head against the roof, and use a very sloping foothold

for one’s feet. As the present writer has never succeeded in getting any

further than this point, he has little knowledge of the rest of the climb.

It looks very hard. The climb was so named after a bet, and legend has

it that the bet was won. If so, half-a-crown seems a wholly inadequate

sum.

Further along than this, nothing but a few scrambles will be found, the best being perhaps a twenty-five foot boulder, which lies off the main path, nearer the road, and behind some cottages.

It should be emphasised that this short list by no means exhausts the practice climbs to be found on Harrison Rocks, but merely enumerates those considered the best, and it is hoped that it may give someone who has never been there an idea of what to expect. Once he has become used to the type of climb to be found here, and the somewhat unusual techniques employed, he will soon notice a large number of other climbs which have not been mentioned; and will find that there is quite sufficient to send him home after a day’s climbing with aching fingers, which are the usual sequel to a visit to Harrison Rocks.