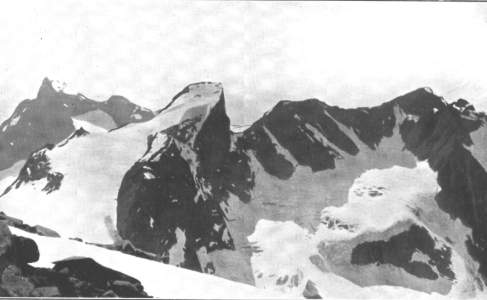

Store Ringstind and Glaciers

THE title of this paper misrepresents its contents, because, whereas in Norway there are many groups of mountains, I am only acquainted with, and can only speak of one; and as to that one – the Horunger group – my experience is limited to two short seasons. Nevertheless I gladly accede to the Editor's request for an article of an ' informative ' nature about these mountains; because, for several reasons, as I think, they deserve to be considered by members of the Cambridge Mountaineering Club in making holiday plans.

First, they are very well adapted for guideless climbing by parties of limited experience. While the rock-climbing is on the whole somewhat harder than that found on ordinary Swiss climbs, the snow and glacier problems are much less serious; and most members of the Mountaineering Club rnust, in the nature of things, be better equipped for rock-work than for snow-craft. Secondly, owing to the comparatively low height of Norse mountains – the limit is about 8,000 feet – and to the fact that in July, which is the best month, the sun is only below the horizon for some two hours, the chances of, and the penalties for, benightment are much slighter than on the greater ranges of the Alps. Thirdly, one is unlikely to experience the horrors of overcrowded huts, or the embarrassment of starting for a climb immediately after or before a guided party. In July, 1913, my companion and I made ' first ascents for the year ' of all the peaks we attempted and were always alone on our mountains Lastly since the process of getting to and returning from Turtegro the chief Horunger centre, occupies, in all, eight days, Norway, if it is to be visited at all, is obviously best visited at a time in one's climbing career when holidays are long. A man tied to business, who only gets off for three weeks, will naturally prefer to go less far afield.

To get to the Horunger a brave man crosses the North Sea to Bergen and then proceeds delightfully up the Sogne Fiord in a Fjord steamer. The coward – to which class I belong – goes by train to Christiania, from which place alternative routes are open to him. At Turtegro, Ole Berge's hotel is very comfortable, and there are several excellent huts in the neighbourhood. Norse young ladies promenading the country in knickerbockers, carrying immense sacks and conversing fluently in English, are frequently on view. My companion in 1913 fell in love successively with three of these ladies, whom we named respectively Una, Secunda and Tertia. Secunda maintained her position for some time after our return to England!

I can best illustrate the nature of the climbing to be had by describing two of our expeditions: and first place, for the sake of honour, must he given to my one and only 39-hour day. We had walked from the boat to a charming spot named Vetti, not far from which is a waterfall 800 feet high; and, after a first day on a local mountain, wished to get to Turtegro. We prepared to do this by way of a not very long pass and set off at 9 o'clock in the morning. After a time we made a mistake as to the route, and found that, in order to get back to it, we should have to descend several hundred feet – a proceeding to which we were both strongly opposed. Straight ahead between us and Turtegro was a big mountain, the Midtmaradalstind, which we knew could be climbed from the other side, so that, if we were able to get up it from where we were, we should eventually reach our destination. We, therefore, set out towards it, crossing on the way a large and attractive glacier upon which reindeer were disporting themselves. The journey was a long one, but we had no difficulty in reaching the top of our mountain. In the direction of Turtegro it stretches out in a long ridge interrupted, after a while, by a vertical drop which it is impossible to pass. On reaching this drop we had to reascend some distance in search of a place at which to turn it. We went down a gully, but the darkness prevented us from noticing a convenient traverse out of it, and we returned to the ridge to bivouac. Our lamp, which was adapted for spirit but charged with oil, refused to function so that, in order to convert a pile of dirty snow into tepid soup, we were constrained to burn under the cooker some hundreds of sheets of paper, with which, fortunately, we were well provided. The night was cold at first, but later we slept to such effect that it was midday before the journey was resumed. In daylight the way along the ridge was easy to find, but, tempted by a plausible gully, we tried to leave it too soon. This gully, in which there was some rock-climbing – interrupted by a stone-fall due to sudden rain – and which we afterwards discoverer1 was virgin, brought us to a glacier, and thence in a violent storm to the hut above Turtegro. Here we spent some hours waiting for the rain to stop and listening to the eloquence of an Englishman whom we found there. He was endeavouring to convince a man and maiden of the country that it would be terribly improper for them to remain in the hut over night unchaperoned by himself! His arguments or, let us hope, a growing conviction in the intending climbers that the next day would certainly be wet, finally prevailed, and the whole party, including ourselves, went down through the rain to Ole Berge's hotel and an admirable midnight meal.

The other expedition, which I shall describe, took place a year later, and was carried out in a less casual fashion. We started from the hotel at 6.30 in the morning – there is no need in Norway to keep Swiss hours ascended first, by an interesting rock-route, the Store (highest) Skagastolstind. After a meal on the top we left about 12:30 and traversed in succession the three summits of the Centraltind, Styggedalstind and Gjertvastind by a splendid series of ridges. As far as the gap between the two last peaks we had fairly clean rock, but for the final ascent had to surmount a slope of frothy and foamlike snow – I have nowhere else met with snow of this character – and some awkward icy chimneys. I have no note of the time at which we reached the top of Gjertvastind, but the ridge walk must have taken at least six hours. The start down was a little difficult to find. Soon, however, we got to snow slopes, leading to a grass track, by which, over a low pass, we returned to Turtegro an hour and a half after midnight. As we entered the hotel, the new dawn was breaking and birds were beginning to sing.

Let me add an incident to show the spirit of the place. On one of our expeditions in 1912 we dropped a rucksack down the mountain side. In the course of his journeys during the following months Ole Berge, the proprietor of the hotel and chief local guide, espied this sack, and decided that mountaineering honour demanded its recovery. He himself made an effort to secure it, but the party he was with were unwilling to descend, and the place was not suited for solitary climbing. On our reappearance next year he was clamorous about our lost possession, and drove us with winged words in pursuit of it. The sack itself, which had contained, among other things, hard boiled eggs, was, I need hardly say, unfit for human society, but we secured a relatively inoffensive specimen of its contents; and this proof of our victory filled the soul of Ole with delight.

It must

not be inferred from the examples which I have given that an average expedition

in the Horunger mountains occupies 39, or even 19 hours. There are short

climbs, moderate climbs and long climbs: for those who desire them, rock-routes

of great severity and horrific ice-gullies which it would take a day to

cut up. Certainly these mountains deserve a visit. If I have succeeded

in tempting anybody to put them on his programme, I shall, of course,

be delighted to tell him anything that I can about them.