In Memoriam

ALFRED VALENTINE VALENTINE-RICHARDS

BY

the death of Alfred Valentine Valentine-Richards Cambridge has lost a

distinguished mountaineer and a man of great kindliness. More than anyone

else he helped to bring the Cambridge University Mountaineering Club to

its present state of vigorous efficiency, and he may well be called the

founder of the less vigorous though equally flourishing Cambridge Alpine

Club.

BY

the death of Alfred Valentine Valentine-Richards Cambridge has lost a

distinguished mountaineer and a man of great kindliness. More than anyone

else he helped to bring the Cambridge University Mountaineering Club to

its present state of vigorous efficiency, and he may well be called the

founder of the less vigorous though equally flourishing Cambridge Alpine

Club.

Valentine-Richards

came up to Christ’s from Uppingham in 1885. He was fourth Wrangler in

1888 and took a first class in the Theological Tripos in 1890. For a short

time after taking his degree he did some lecturing work in Cambridge,

and then for a number of years lived at his home in Wimbledon and spent

much time abroad. It was during these years that he acquired his skill

as a mountaineer and amassed his wide knowledge of Alpine matters. He

returned to Christ’s as a fellow and lecturer in 1904 and became dean

in 1906.

We of a

younger generation who knew him in the years that followed, were well

aware of the vast storehouse of mountain knowledge that was his, but it

was only rarely that he spoke of his own climbing exploits. It is a pity

that there is so little in print about his early climbing expeditions.

His articles in the Alpine Journal are masterpieces of accurate

information and detail; but one could wish that he to whom the mountains

made such an appeal had left more on record of the joy and feeling that

they aroused in him.

It requires

a particular bent of mind to keep pace with and co-ordinate the various

developments of Alpinism. Valentine- Richards possessed the necessary

critical capacity and pains- taking accuracy in a high degree, and when

the Alpine Club decided to bring Ball’s Alpine Guide up to date

as a memorial to its first president, it fell to Valentine-Richards to

take in hand the general editorship of The Central Alps, Part I.

Anyone familiar with this great guide – the model perhaps for all mountain

guide-books – will appreciate the immense amount of labour that must have

gone to its re-editing. Valentine- Richards began his task in 1901 and

his volume was published.

In the years

that followed his return to Cambridge he became the friend of generation

after generation of under- graduates. He continued to spend his summers

in the Alps and often took undergraduates with him. He also took parties

to North Wales and the Lake District. He was the ideal com- panion as

all who have memories of those delightful holidays will agree. His activity

and energy amazed the younger members of these parties. Often the expeditions

were pro- longed to surprisingly late hours and it was long after night-

fall when we tramped back over the fells after the rock- climbing had

been done. It was a point of his never to be benighted, and I think he

succeeded in this, though I remember one day getting down to Langdale

at 3 a.m., after some wet climbs on Scafell and a delay of several hours

on the Pike in mist and complete blackness. To all who climb the rocks

must become a measure of the passing of years, and in those days Valentine-Richards

preferred not to lead rock climbs; but there could never have been a more

helpful and patient second on a rope. Sometimes, perhaps, too much patience

was demanded of him, as on one occasion when a leader in order to renew

his attack on the top block of the Napes Needle adopted a surprising and

rapid, though perhaps not uncontrolled, slithering descent to the shoulder

below. I think it was good advice of Valentine-Richards to leave the Needle

for that day and to pass on to the Needle Arête.

In the War

years there was the inevitable break in his visits to the hills. He turned

his activities to the Boy Scouts, and scouting became one of his chief

interests throughout his latter years – indeed, he carried on his camping

with scouts when it seemed almost impossible that his health was good

enough to stand it.

When Cambridge

revived after the War Valentine-Richards at once got together a nucleus

to reform the Cambridge University Mountaineering Club. Numbers rapidly

increased until by degrees the club has reached the big membership it

now has. When numbers were smaller the club frequently met in Valentine-Richards’s

rooms in Christ’s. He was the perfect host for such gatherings, which

were rather more informal and certainly less ambitious as regards discourses

than is now the case. It was a great privilege that the club should have

held so many of its meetings in his delightful rooms. There was much in

the surroundings there – his Alpine books, his pictures, his fine collections

of furniture and china which conduced, more perhaps than one was conscious

of at the time, to make these meetings so successful. I know it was a

great happiness to Valentine-Richards in the days when his climbing career

was drawing to a close to have so many young mountaineers coming to him.

His help was inestimable. The club is largely his achievement and is the

outcome of bis mountain knowledge and experience.

He had a

few summers in the Alps in the post-War years. Once he was at Saas Fee,

where he was particularly pleased with what he was still able to do, and

.html year he went to the Belvédère (Furka); but in 1924

when he last visited Kandersteg it became clear that he was no longer

equal to the exertion of long mountain days.

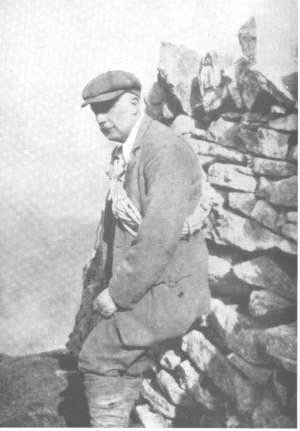

The photograph

which accompanies these lines was taken in April 1923,.at the top of the

slabs on Carnedd y Filiast, the last spring holiday in which Valentine-Richards

did any rock climbing.

During the

remaining years of his life he suffered from an illness which made it

increasingly difficult for him to get about. However, he was active in

lecturing and other Cambridge duties until his death last April at the

age of 66.

In what

I have written I have had Valentine-Richards the mountaineer in view.

Others will remember him in other ways, with affection as a most approachable

dean of their College, or for his scholarship in theological matters.

Some will recall him as a connoisseur and collector of china, glass, and

silver, and for his keen interest in gardening and flowers. He had wide

interests which led him into many pleasant paths, and his joy in the mountains

and his great love for them inspired him in all that he did. C. M. S.

HENRY GEORGE

WATKINS

HON. TREASURER

OF THE CLUB, 1927 – 28

WATKINS

began his climbing career while still at school at Lancing, going to the

Lake District in April 1924 with one of the masters, Mr. E. B. Gordon.

Both were beginners, and his companion emphasizes that of the two it was

Watkins who provided the necessary enterprise, chose climbs, and acted

as leader. Opportunities in the Alps came the same year, when he was at

Chamonix with his parents. Mr. Gordon joined him, and together they climbed

the Grands Charmoz and the Aiguille de l’M. In 1925 he was again in Switzerland

and made some climbs, among them the traverse of the Petite Dent de Veisivi,

with Emile Gysin, a student of nineteen who hoped to qualify in time for

his guide’s certificate. Later in the same year Watkins was chamois hunting

with his father in Tyrol, and had a narrow escape, falling 150 ft. down

steep rocks.

His big

Alpine year was 1926, when he spent over six weeks almost entirely with

Gysin. Watkins wrote out a list of his expeditions in Gysin’s diary, from

which it appears that they followed a more or less high level route from

Chamonix to Zermatt, the order of events being roughly: Aiguille du Moine,

Aiguille de la Persévérance, Aiguille de la Neuvaz, Pointe

des Amethystes, Aiguilles du Tour, Aiguilles Marbrées, traverse

of Mont Grépillon and Mont Dolent, Grand St. Bernard, Mont Velan,

Col des Maisons Blanches, La Ruinette, and various passes via Arolla and

Zinal to St. Nicolas and Zermatt; traverse of Monte Rosa from Bétemps

Hut to Macugnaga, and back by New Weissthor and Cima di Jazzi; Aiguille

de la Tsa and Pigne d’Arolla; and later on Mont Blanc and the Grands Charmoz.

My own friendship

with Watkins dates from the spring of 1926, and our mutual interest was

in Arctic rather than Alpine matters. Watkins received his Arctic inspiration

from R. E. Priestley’s lectures, given at Cambridge intermittently from

1923 to 1930, a course which it is hoped may be revived again soon in

some form or other. I had planned an Arctic expedition for 1927 with Watkins

as a member, but when it was postponed Watkins immediately decided to

lead a party himself. He was then twenty. He chose Edge Island in East

Spitsbergen as his objective, and chartered the motor sloop Heimen

of Tromsö for his party of nine. They explored and mapped parts of

Edge Island, and found unexpectedly that the interior was not completely

ice-covered as formerly thought. This caused an important change in Watkins’s

plans; he had hoped to sledge across the island, but the actual crossing

of the interior was in the end made on foot.

On his return

he decided almost immediately to visit Labrador in 1928, and to remain

over the winter. His companion was J. M. Scott, and together they learnt

how to travel by canoe and dog sledge. Watkins returned from his training

year in Labrador unusually well-equipped for extended Arctic explorations.

Plans for

a great Greenland Expedition were made, and in July 1930 Watkins took

a party of fourteen, constituting the British Arctic Air Route Expedition,

to winter on the east coast near Angmagssalik. Several hundred miles of

the coast were explored in detail for the first time, partly by ship,

partly from the air. On one of the flights Watkins sighted an entirely

new range of mountains in 69°N. latitude, the highest in the Arctic, estimating

their height at 12,000-15,000 ft. (Last year – 1933 – this range was actually

flown over by Colonel Lindberg, who assigns a definite height of 13,000

ft.) The Greenland ice cap was crossed by two sledge parties in the early

summer of 1931, one to Ivigtut, the other to Holsteinborg. There had also

been an attempt in spring to climb Mount Forel, over 11,000 ft., L. R.

Wager leading a party to within about 700 ft. of the summit. Watkins concluded

the explorations by making a hazardous boat journey with two companions

round Cape Farewell to Julianehaab. On his return he was awarded the gold

medal of the Royal Geographical Society as a tribute to his leadership

of the most important Arctic expedition which had gone from this country

since 1875.

Watkins’s

last expedition was made a year later when he returned to East Greenland,

this time with only three companions, to complete the necessary groundwork

for the Arctic air route. In August 1932, a few weeks after arriving on

the coast, he was drowned while hunting from his kayak; no details are

known, except that some chance must have made it necessary for him to

take to the water, and that he was overpowered by the cold before being

able to regain his kayak.

Watkins

must have made an ideal climbing companion. Mr. Gordon says of him that

he "was an enterprising climber and cautious, as I suppose the best climbers

always are." Gysin refers particularly to his powers of endurance, to

his prudence, and to his aptitude for rapid decision when necessary.

These are

among the special qualities demanded of an Arctic leader, and Watkins

succeeded in leadership in a marked degree. He chose his men well and

trusted them, giving them a wide latitude in all they did. He was always

ready willing at any time to modify his plans as hindrances occurred or

new opportunities appeared. These were some of the secrets of his success,

which places him in the front rank of Polar leaders, with McClintock,

with Shackleton, and with Nansen. J. M. W.

JOHN DAVID

BEST

DAVID BEST,

who joined the club as soon as he came up to Queens’ in1928, and was one

of its most active supporters, was Secretary in his last year (1930-31).

As a boy

he had lived in the Pennines and been at school al Kendal, so that he

had ample opportunity of taking advantage of the fells that attracted

him so much, and he was lucky enough to be able to begin rock-climbing

much sooner than most people. His enthusiasm for climbing was as boundlessly

ambitious as it was for anything else that interested him. He always aimed

at something better and more exciting, but not without fully appreciating

what he was actually able to do; probably he enjoyed, more than any of

his later climbing, his early expeditions from school to Sleddale, where

he explored almost unknown crags on summer half-holidays.

As a result

of his remarkable keenness, by the time he came up to Cambridge, Best

was one of the most capable and agile rock-climbers in the club, and it

was only the difficulty of his going out to the Alps more often that prevented

him from becoming as accomplished a mountaineer as he was a rock- climber.

He was a fearless climber, who always took it for granted that he could

get up anything that confronted him, but he never gave the impression

that he was climbing near his margin of safety, and his own confidence

inspired unexpected success in his more timid companions.

After taking

honours in Mathematics and Engineering, Best worked for the Gaslight and

Coke Company before joining the Air Force, and it was only a year after

he went down that he was killed in a flying accident. His early death

has robbed us, his climbing friends, of a delightful companion and has

spoilt, almost before it had begun, a mountaineering career which showed

every sign of being a very remarkable one. C. B.

GEORGE

HEWLETT DAWES EDWARDS

HEWLETT

EDWARDS came up to St. John’s in 1931, and the following year proceeded

to Westcott House, with the intention of taking orders. He came of a family

whose members have all shown a natural aptitude for climbing and, indeed,

he might well have been one of the most brilliant climbers of his day,

had he taken the sport seriously, for he combined just that right amount

of dash and restraint which form the essential make-up of a great leader.

His work at Cambridge, however, precluded all but occasional visits to

the mountains.

It was when

returning from one of these visits that he was involved in a motor-cycle

accident, and received head injuries to which he succumbed some three

hours later. The previous afternoon he had made a solitary descent of

the Devil’s Kitchen, no slight achievement, as those familiar with Welsh

rocks will admit.

Although

he had been a member of the C.U.M.C. since he first came to the University,

he had attended only one meet, that at Helyg in January 1933, and few

members of the club knew him well. Only those of us who were his intimate

friends and enjoyed his delightful companionship can realize how great

a loss the club has suffered in the death of a man who was so sound in

every way. S. B. D.

BY

the death of Alfred Valentine Valentine-Richards Cambridge has lost a

distinguished mountaineer and a man of great kindliness. More than anyone

else he helped to bring the Cambridge University Mountaineering Club to

its present state of vigorous efficiency, and he may well be called the

founder of the less vigorous though equally flourishing Cambridge Alpine

Club.

BY

the death of Alfred Valentine Valentine-Richards Cambridge has lost a

distinguished mountaineer and a man of great kindliness. More than anyone

else he helped to bring the Cambridge University Mountaineering Club to

its present state of vigorous efficiency, and he may well be called the

founder of the less vigorous though equally flourishing Cambridge Alpine

Club.